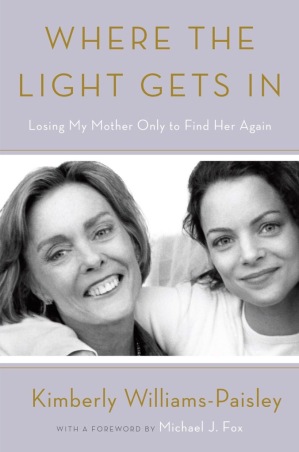

There are two beautiful faces and one famous name on the cover of this book, but please don’t think of it as a “celebrity memoir.” Instead, consider Kimberly Williams-Paisley’s Where the Light Gets In a map to the unmappable: a candid account of one family’s experience through the nightmare of a parent’s illness.

Williams-Paisley’s mother, Linda Williams, was diagnosed at age 62 with primary progressive aphasia, a rare form of dementia. In a cordial tone and clear prose (not surprising, given that she was raised by journalists) Williams-Paisley offers up the mistakes and discoveries her family made as they navigated this huge change to their family dynamic, infusing her story with funny anecdotes and bright moments that keep it engaging, even entertaining. Our booksellers love it. (It’s Sissy’s staff pick for April.)

As Ann Patchett wrote here recently, “Memoirs have a lot to teach us.” What we learn from Where the Light Gets In is this: “Over the years, there are a series of arrivals and departures . . . the challenge is encouraging the people we love to become independent, and to love them as they are.” For anyone caring for an ill or aging loved one — anyone who is part of a family at all, for that matter — that lesson comes as a tremendous gift.

In this interview with our editor, Mary Laura Philpott, Williams-Paisley discusses how she wrote the book and what she hopes it will accomplish. Meanwhile, we hope you’ll make plans to join us for the reading next Tuesday, April 19, at 6:15 at the Nashville Public Library.

Tell me about the title.

Tell me about the title.

KWP: It came to me one morning toward the end of writing the book. I’d gone over different titles, looking at things like “Riding the Storm,” but everything felt too dramatic. Then a woman named Nancy — of course you know who that is now, because you meet her in the book, but she wasn’t in the picture in the beginning — sent me a lyric from the Leonard Cohen song Anthem, which I loved:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

I wrote it down and put it on my mirror, and I knew that was my anthem for this book, where I’m showing all my warts and flaws. That idea of letting light shine through the cracks, letting light in through the hard parts. It hit me one morning: this is the title.

How long did the book take you to write?

KWP: About a year and a half. I started writing in July of 2014, and I only worked on it a few hours a day. Some days I took off.

Are you one of those people who can get up super-early in the morning to write?

Noooooo. [laughs] Not a bit. Writing this book was a wonderful job. I’m used to having to get on a plane to go to work when I’m acting. When I was writing, I could see the kids in the morning, then walk the dogs, then go into my office for a couple of hours. Then when I got stuck or when it was too hard, I could take a break. I found that giving myself a lot of air in the process helped everything percolate.

To what extent is writing in your comfort zone — or out of it?

KWP: I love writing! I started writing when I was eight years old. A family friend gave me a journal and I took right to it. I thought I was very important — I had a lot to write about. It was always a way for me to process and figure out what I thought. And I grew up in a family of writers; I was surrounded by it. Those were my favorite classes in school, too. I had multiple English teachers in high school who were fantastic, and then I took journalism classes at Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern. I always toyed with dropping this acting thing and becoming a writer.

You wrote in the book that as the oldest in your family — the people pleaser and “parent pleaser” — you had a different response when your mother first started showing signs of dementia than Jay and Ashley, your siblings, did.

KWP: I did not crumble under the pressure, because I didn’t allow myself to feel what was happening in the beginning. I approached it from a more practical point of view. My sister approached it practically also, in that she did a lot of research, but she also allowed herself to feel it. She’s very emotional, and I admire that about her. Sometimes I worry I’m too closed-off emotionally. I also came at it with a heavy dose of denial.

Between the time when I first read the manuscript and now, photos have been added to the book. How did you choose those?

KWP: That was fun! I love the picture of my mom and me on the cover. Initially, I had looked at using another one, but it was too stiff and formal — it didn’t really capture the essence of my mom. That picture that’s on the cover now is really her. The last picture in the book always makes me gasp — I just lose my breath. You turn the last page, and there’s my mom, from behind, looking up, with her arms up in the air to the sky. She always did that. I love that it got in there.

You had your sons as the early years of your mom’s illness were unfolding. Could you sense at the time the parallels between caring for your parents and caring for young children?

KWP: I could — and it was really disarming, because I was trying to protect everybody. That’s where being the oldest child really kicked in. I was trying to juggle a lot of balls and protect my mom and protect my children, and protect my children from my mom, and trying to protect my mother’s pride. I could hardly breathe from all that pressure. It was exhausting and scary trying to guess all the time what the next move was. My mother was so unpredictable. The kids were actually more predictable than she was.

You write about a moment when your mom almost dropped your infant son, and how your first gut reaction wasn’t compassion or worry but anger at your mom. I appreciated that you were willing to show the reality of how frustrating it was for you, even though it was painful to remember. Were there any stories that were too difficult to write about?

KWP: Well, it’s more that I got to a point where I was like, OK, people aren’t going to want to hear another story of my mom walking naked down the hall or knocking things over and embarrassing herself. It’s redundant. There are way more stories than I included. But that was part of the trick — cutting out what we didn’t need and keeping in what’s necessary and valuable.

You tell the story of how your parents made “parachute books” full of empowering mementos for you and your siblings when you graduated and went out into the world, and how you brought that tradition back for your mom and gave her a scrapbook showing her how loved she was when she got sick. Were there actual books that served as “parachutes” for you during this experience? Things you read that you found particularly relatable or helpful?

KWP: That’s a good question. Honestly, a lot of it I couldn’t stomach. It took me a long time to read Still Alice. That was given to me early on, at a time when I couldn’t handle it. I didn’t want to visit those stories then.

I definitely felt like we didn’t have the roadmap I wanted. I can think of a lot I’ve read since then that would have been helpful. Like When Breath Becomes Air, which is so beautiful. And Being Mortal — which I wish had been written 10 years ago. It has the questions you’re supposed to ask when someone gets sick, what you’re supposed to ask your doctor. That would have helped us so much.

It seems like a little light broke through when you realized your mom had reached a point where she was truly living in the moment. Does it alleviate some of your own anxiety to know that she’s not feeling the same kind of anticipatory fear you are?

KWP: It does. I’m glad that she doesn’t appear to be in physical pain. I do sense that there’s an existential sort of pain she feels. But there’s so much I don’t know, so I’m sort of embracing the mystery. What I imagine, what I gather from her doctors, is that she’s having dream-like states where she’ll have a flash of something happy, a flash of something scary, a flash of something sad, a flash of anger — but they’re only flashes, and they’re in the moment, so once they’re gone, she’s in another moment. That is somewhat of a relief. But there’s so much unknown.

The resources section at the end was a brilliant addition.

KWP: That was my dad’s idea. It came from conversations he had with the Alzheimer’s Association. Early on, he said, “There aren’t a lot of books out there with this kind of story that also have a practical part.” We wanted to give people not just this narrative but also this thing we didn’t have — a list of questions to ask and steps to take and resources to consult. Not everyone will even look at that section, but the people who need it will have it. And it’s not just for people dealing with dementia. There are tons of caregivers out there.

Will you write more?

KWP: I would love to. I don’t know what the story would be next.

What else are you up to these days, creatively?

KWP: I’m developing a TV show for the Hallmark Channel, which is the fastest growing cable channel, so that’s fun. It’s a family legal drama, and I’m working with a great writer. I’m not writing that one though, just acting — I want to get back to that.

How do you like living in Nashville?

KWP: Nashville is a really fun place to be right now, don’t you think? Brad and I have been married 13 years, and we knew each other a couple of years before that, so Nashville has been in my life for about 15 years. It has changed so much in that time. It always had the music, of course, but it didn’t have the restaurant scene or quite this level of influx of people and culture and art. There’s so much to see and do. We just went to the zoo — it was a blast. I love getting involved in the community here. I find that I’m really busy, in a good way. It’s a great place to raise kids.

What do you love most about the real-live bookstore experience?

KWP: I love the smell of books and bookstores.

People always say that.

KWP: It’s true! You can’t get that from your Kindle. I love going into bookstores and discovering something I never would have known about before. I love taking my kids to bookstores. We’ve discovered some great books at Parnassus and had some great experiences because of those books. Books have led us on journeys and led to other books. It’s neat, too, to have people who know what you’ve read and what you’ve liked who can say, “Well, if you liked that, here are five other things you can read.” I buy a lot of books.

* * *

Where the Light Gets in: Losing My Mother Only to Find Her Again

Where the Light Gets in: Losing My Mother Only to Find Her Again

Ticketing and book-signing details: This FREE, ticketed presentation is part of the Salon@615 series, offered to the public by a partnership of Parnassus Books, Humanities Tennessee, The Nashville Public Library and Foundation, and BookPage. Advance auditorium tickets are limited and guarantee a seat in the auditorium. A limited number of auditorium tickets will also be available on-site 30 minutes before showtime on the event date. We recommend arriving early for the on-site ticket line. BONUS: A book signing will be held after the presentation for anyone who purchased a copy of this book from Parnassus Books! Copies will be available for purchase at the event. (As a Salon patron, you will receive a 10% discount!) Details here.